BIOGRAPHY OF GEORGES LEMAITRE (1894-1966)

-

born July 17, 1894, Charleroi, Belgium.

died June 20, 1966.

|

|

BIOGRAPHY OF GEORGES LEMAITRE (1894-1966)

died June 20, 1966. |

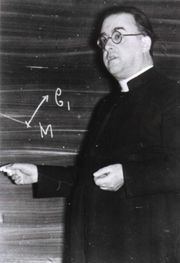

Georges-Henri Lemaitre (1894-1966) showed that religion and science -- or at least physics -- did not have to be incompatible. LeMaitre, born in Belgium, was a monsignor in the Catholic church.

Both a priest and a cosmologist, Georges Lemaitre, perhaps not unexpectedly, spent much of his career studying the origin of the universe. After a stint as an artillery officer in the Belgian army during World War I, he entered a seminary and was ordained a priest in the early 1920s. Shortly after, however, his interest in astronomy brought him to Cambridge University in England and then to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. While there, he became captivated by the new idea of an expanding universe. He reasoned that if the universe was expanding now, then the further you go in the past, the universeís contents must have been closer together. He envisioned that at some point in the distant past, all the matter in the universe was crushed into a single object he called the ěprimeval atom.î This primeval atom then exploded, with all its constituent parts rushing away. His basic idea has become the most widely accepted model for how the universe originated, what we today call the Big Bang.

He was fascinated by physics and studied Einstein's laws of gravitation, published in 1915. He deduced that if Einstein's theory were true (and there had been good evidence for it since 1919), it meant the universe must be expanding.

In the meantime, in 1925, Lemaitre took a position as a part time lecturer at the Universite' Catholique de Louvain (UCL).

It was here he began down the path towards the thesis that would bring him to the attention of the world.

In 1927, he accepted a full time position at UCL and released his work entitled:

Un Univers homoge`ne de masse constante et de rayon croissant rendant compte de la vitesse radiale des ne'buleuses extragalactiques

(A homogeneous Universe of constant mass and growing radius accounting for the radial velocity

(radial velocity: Velocity along the line of sight toward or away from the observer) of extragalactic nebulae).

This paper explained the expanding universe in a new way, and within the framework of the General Theory of relativity.

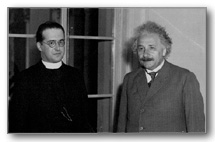

Initially, many scientists, including Albert Einstein, himself, were skeptical. However, further studies by Edwin Hubble,

seemed to prove the theory. Initially called the "Big Bang Theory" by its critics, the name eventually stuck.

Even Einstein was won over, standing and applauding at a Lemaitre seminar, saying "This is the most beautiful and

satisfactory explanation of creation to which I have ever listened."

Lemaitre’s theory didn’t immediately win a lot of converts. Einstein, for one, remained unconvinced. It wasn’t until Edwin Hubble discovered that almost every galaxy was rushing away from Earth— and that the farther away the galaxy, the faster it was receding—that Einstein came around. Although Lemaitre’s conception of the Big Bang was prophetic in many ways, his idea about the initial state of the universe is almost the polar opposite of what we think today.

Instead of a complex initial structure that broke apart to form the universe’s basic constituents, scientists now believe that the universe started out very simple and then grew more complex as it evolved. That idea first came from the Russian-born American physicist George Gamov in the 1940s. Working with his student Ralph Alpher, he envisioned the universe beginning with an extraordinarily hot Big Bang. As the universe expanded, this superhot primordial soup of protons, neutrons, electrons, and radiation grew steadily cooler, and the constituents began fusing into heavier elements. Helium formed first, followed by all of the heavier elements, with the process wrapping up within about half an hour.

Lemaitre's ideas opened more questions, many of which forced physics and astronomy together: What was that primordial atom like? Why would it explode? He pursued the topic for some time, even suggesting that there ought to be some form of background radiation in the universe, left over from the initial explosion of that primordial atom. He became more interested in the philosophical ramifications of his theory, which were many. Others took up the big bang theory, and for several years there were strong debates between those supporting it and those who favored a "steady state" theory of the universe, in which the universe was eternal and unchanging. This argument ended when Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson found evidence of cosmic background radiation, which Lemaitre and other theorists had determined would be the residue of the big bang's explosion many billions of years ago.

Georges-Henri Lemaitre continued to advance science throughout his life. He studied cosmic rays and worked on the three-body problem. His published works include Discussion sur l'e'volution de l'univers (1933; “Discussion on the Evolution of the Universe”) and L'Hypothe`se de l'atome primitif (1946; “Hypothesis of the Primeval Atom”). On March 17, 1934, he received the Francqui Prize, the highest Belgian scientific distinction, from King Le'opold III, for his work on the expanding universe. In 1941, he was elected member of the Royal Academy of Sciences and Arts of Belgium. In 1941, he was elected member of the Royal Academy of Sciences and Arts of Belgium. In 1950, he was given the decennial prize for applied sciences for the period 1933-1942. In 1953 he received the very first Eddington Medal award of the Royal Astronomical Society. In 1953 he was given the very first Eddington Medal award of the Royal Astronomical Society. During the 1950s, he gradually gave up part of his teaching workload, ending it completely with his emeriture in 1964.

In 1936, he was elected member of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences.

He took an active role there, became the president in March 1960 and remaining so until his death.

At the outset of the Second Vatican Council, he was bemused to find himself appointed by the Pope to sit on a commission

investigating the subject of birth control. He was also named prelate (Monsignor) in 1960 by Pope John XXIII.

At the end of his life, he was devoted more and more to numerical calculation. He was in fact a remarkable algebraicist and arithmetical calculator. Since 1930, he used the most powerful calculating machines of the time like the Mercedes. In 1958, he introduced at the University a Burroughs E 101, the University's first electronic computer. Fr. Lemai^tre kept a strong interest in the development of computers and, even more, in the problems of language and programming. With age, this interest grew until it absorbed him almost completely.

He died on June 20, 1966 shortly after having learned of the discovery of cosmic microwave background radiation, proof of his intuitions about the birth of the Universe.

There are a few places where the biography of GEORGES LEMAITRE can be found.

Wikipedia electronic Encyclopedia(http://en.wikipedia.org/) , an article Georges Lemaitre.

CATHOLIC EDUCATION RESOURCE CENTER.