Schrodinger was an unconventional man. Throughout his life he traveled with walking-boots and

rucksack and for this he had to face some difficulty in gaining entrance to the Solvay Conference for

Nobel laureates. Describing the incident Paul Dirac wrote: When he went to the Solvay Conferences in

Brussels, he would walk from the station to the hotel, carrying all his luggage in a rucksack and

looking so like a tramp that it needed a great deal of argument at the reception desk before he could

claim a room.

Schrodinger was born on August 12, 1887 in Vienna. His father Rudolf Schrodinger, who came

from a Bavarian family, which had come to Vienna generations ago, was a highly gifted man.

After studying chemistry at the Technical College in Vienna, Rudolf Schrodinger devoted himself

for years to Italian painting and then he decided to study botany. He published a series of research

papers on plant phylogeny.

Rudolf Schrodinger had inherited a small but profitable business manufacturing linoleum and oilcloth.

Schrodinger mother, Georgine Schrodinger (nee Bauer) was the daughter of Alexander Bauer, an

able analytical chemist and who became a professor of chemistry at the Technical College, Vienna.

Schrodinger was always grateful to his father for giving him a comfortable upbringing and a good

education. He described his father as a man of broad culture, a friend, teacher and inexhaustible

partner in conversation.

Schrodinger was taught by a private tutor at home until he entered the Akademisches Gymnasium in 1898.

He passed his matriculation examination in 1906. At the Gymnasium, Schrodinger was not only

attracted to scientific disciplines but also enjoyed studying grammar and German poetry. Talking

about his impression at the Gymnasium Schrodinger later said: I was a good student in all subjects,

loved mathematics and physics, but also the strict logic of the ancient grammars, hated only memorizing

incidental dates and facts. Of the German poets, I loved especially the dramatists, but hated the

pedantic dissection of their works. He was an outstanding student of his school.

He always stood first in his class. His intelligence was proverbial. One of his classmates commenting

on Schrodinger ability to grasp teachings in physics and mathematics said: Especially in physics and

mathematics, Schrodinger had a gift for understanding that allowed him, without any homework,

immediately and directly to comprehend all the material during the class hours and to apply it.

After the lecture…it was possible for (our professor) to call Schrodinger immediately to the

blackboard and to set him problems, which he solved with playful facility.

In 1906, Schrodinger joined the Vienna University. Here he mainly focused in the course of theoretical

physics given by Friedrich Hasenohrl, who was Boltzmann student and successor. Hasenhorl gave an

extended cycle of lectures on various fields of theoretical physics transmitting views of his teacher,

Boltzmann.

Schrodinger received his PhD in 1910. His dissertation was an experimental one. It was on

humidity as a source of error in electroscopes. The actual title of the dissertation

was

On the conduction of electricity on the surface of insulators in moist air. The work was

not very significant. The committee appointed for examining the work was not unanimous in

recommending him for the degree. After receiving his PhD, he undertook his voluntary military service.

After returning from military service in autumn 1911, he took up an appointment as an assistantship

in experimental physics at the University of Vienna. He was put in charge of the large practical

class for freshmen. Schrodinger had no love for experimental work but at the same time he valued the

experience. He felt that it taught him through direct observation what measuring means. He started

working in theoretical physics by applying Boltzmann-like statistical-mechanical concepts to magnetic

and other properties of bodies. The results were not very significant. However, based on his work

he could earn his advanced doctorate (Habilitation).

At the beginning of the First World War, Schrodinger was called up for active service. He was sent

to the Italian border. It was at the warfront that Schrodinger learned about Einstein general

theory of relativity and he immediately recognized its great importance. While in war field it was

not possible for Schrodinger to keep him fully abreast of the developments in theoretical physics.

However, he continued his theoretical work. He submitted a paper for his publication from his position

on the Italian front. In the spring of 1917, Schrodinger was transferred to Vienna, where he again

could start scientific work.

The First World War resulted in total collapse of the economy of Austria. It also ruined Schrodinger

family. Schrodinger had no option other than to seek a career in the wider German-language world of

Central Europe. Between spring 1920 and autumn 1921, Schrodinger took up successively academic

positions at the Jena University (as an assistant to Max Wien, Wilhelm Wien brother, at the

Stuttgart Technical University(extraordinary professor), the Breslau University (ordinary professor),

and finally at the University of Zurich, where he replaced von Laue. Soon after arriving at Zurich,

Schrodinger was diagnosed with suspected tuberculosis and he was sent to an alpine sanatorium in

Arosa to recover. While recuperating at Arosa, Schrodinger wrote one of his most important papers,

On a Remarkable Property of the Quantized Orbits of an Electron. At Zurich he stayed for

six years. This was his most productive and beautiful period of his professional life.

It was at Zurich that Schrodinger made his most important contributions. He first studied atomic

structure and then in 1924 he took up quantum statistics. However, the most important moment of his

professional career was when he came across Louis de Broglie work. On November 03, 1925,

Schrodinger wrote to Einstein: A few days ago I read with great interest the ingenious thesis

of Louis de Broglie, which I finally got hold of ... And then on 16th November he wrote:

I have been intensely concerned these days with Louis de Broglie ingenious theory.

It is extraordinarily exciting, but still has some very grave difficulties. After reading de Broglie

work Schrodinger began to think about explaining the movement of an electron in an atom as a

wave and eventually came out with a solution. He was not at all satisfied with the quantum

theory of the atom developed by Niels Bohr, who was not happy with the apparently arbitrary

nature of a good many of the quantum rules. Schrodinger did not like the generally accepted dual

description of atomic physics in terms of waves and particles. He eliminated the particle altogether

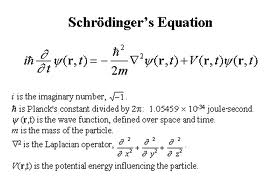

and replaced it with wave alone. His first step was to develop an equation for describing the movement

of electrons in an atom. The de Broglie equation giving the wavelength \Lambda=h/mv (where h is the Planck

constant and mv the momentum) represented too simple a picture to match the reality particularly with the

inner atomic orbits where the attractive force of the nucleus would result in a very complex and variable

configuration. Schrodinger eventually succeeded in developing his famous

wave equation. His equation was very

similar to classical equations developed earlier for describing many wave phenomena — sound waves, the

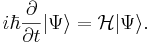

vibrations of a string or electromagnetic waves. In Schrodinger wave equation there is an abstract entity,

called

the wave function and which is symbolized by the Greek letter \psi (psi). When applied to the

hydrogen atom, Schrodinger wave equation yielded all the results of Bohr and de Broglie. However,

despite the considerable predictive success of Schrodinger wave mechanics,

Schrodinger had to overcome certain problems. First problem was how to attach certain physical

meaning to an electron if it (wave function) was nothing but wave. Also he had to show what

exactly represented by the wave function.

Schrodinger worked hardly to account these questions. He tried to visualize electron

as

wave packets made up of many small waves so that these wave packets would behave in the same

way as a particle in classical mechanics. However, these packets were later shown to be unstable.

He interpreted the wave function as a measure of the spread of an electron. But this was also not

acceptable. The interpretation was provided by Max Born. He stated that the wave function for a

hydrogen atom represents each of its physical states and it can be used to calculate the probability

of finding the electron at a certain point in space (

the probability amplitude). What does it mean? It means that if the

wave function is nearly zero at a certain point then the probability of finding the electron there

is extremely small. But where the wave function is large the probability of finding the electron is

very large. The wave mechanics cannot be used to determine the motion of a particle or in other words

its position and velocity at any given moment. The wave equation simply tells us how the wave function

evolves in space and time and the value of the wave function would determine the probability of

finding the electron in a particular point of space.

He published his revolutionary work in a series of papers in 1926. Schrodinger wave equation

was the second theoretical explanation for the movement of electrons in an atom, the first

being Werner Heisenberg matrix mechanics. Schrodinger approach was preferred by many physicists

as it could be visualized. On the other hand Heisenberg approach was strictly mathematical and it

involved such a complex mathematics that it was difficult to understand. Physicists appeared to be

divided into two groups. However, soon Schrodinger showed that the two theories were identical but

expressed differently.

Schrodinger students at Zurich found his lectures extremely stimulating and impressive.

One of his students, who attended his lectures, later recalled: At the beginning he stated the

subject and then gave a review of how one had to approach it, and then he started exposing the

basis in mathematical terms and developed it in front of our eyes. Sometimes he would stop and

with a shy smile confess that he had missed a bifurcation in his mathematical development,

turn back to the critical point and start all over again. This was fascinating to watch and we all

learned a great deal by following his calculations, which he developed without ever looking at

his notes, except at the end, when he compared his work on the blackboard with his notes and

said this is correct. In summertime when it was warm enough we went to the bathing beach on the

Lake of Zurich, sat with our own notes on the grass and watched this lean man in bathing trunks

writing his calculations before us on an improvised blackboard which we had brought along. At the

time few people came to the bathing beach in the morning and those that did watched us from a

discreet distance and wondered what that man was writing on the blackboard.

After the retirement of Max Plank from Berlin University as Professor of Theoretical Physics,

three persons were short-listed for the post: Sommerfeld, Schrodinger and Max Born.

Schrodinger testimonial drawn up for the purpose beautifully summarised his academic achievements

till that time. It said: For some years already he has been favourably known through his versatile,

vigorously powerful, and at the same time very profound style in seeking new physical problems that

interested him and illuminating them through deep and original ideas, with the entire set of techniques w

hich mathematical and physical methods at present provide. He has proved this method of working to be

effective in the treatment of problems in statistical mechanics, the analysis of optical interference,

and the physical theory of colour vision. Recently he has succeeded in an especially daring design

through his ingenious idea for the solution of the former particle mechanics by means of wave mechanics

in the differential equation he has set up for the wave function. Schrodinger himself has already been

able to deduce many consequences from this fortunate discovery, and the new ideas that he has inspired

with it in many fields are even more numerous ... it may be added that in lecturing as in discussions

Schrodinger has a superb style, marked by simplicity and precision, the impressiveness of which is

further emphasized by the temperament of a South German. Sommerfeld was the first choice and when he

declined to leave Munich the offer went to Schrodinger. Even for Schrodinger it was not easy for taking

a decision to leave Zurich. Ioan James has written: Every effort was made to persuade him to stay in

Zurich. The physics students organized a torchlight parade around the university to the courtyard of

his house, where they presented him with a petition. Schrodinger was deeply moved, but in the end it

was a personal appeal from Planck that persuaded him to accept the Berlin offer; as the result of doing so

he automatically became a German national. Before taking up the appointment at Berlin, Schrodinger traveled to

Brussels to attend the Solvay physics conferences. This time the topic was electrons and photons. Schrodinger was

invited to deliver one of the prestigious lectures. He took this opportunity to elaborate on his

wave mechanics. His views caused considerable debate. Born and Heisenberg attacked it quite

vehemently.

Schrodinger joined the Berlin University on October 01, 1927, where he became a colleague of

Albert Einstein. The course given by him at the Berlin University was considered the best among the

science courses at the University. His style of lecturing was informal. He lectured without notes

while many professors at the University practically read their lectures. His dress was also quite

informal compared to other professors. He was elected to the Berlin Academy of Science at the age

of forty-two. He happened to be youngest member of this august body.

Like many other scientists Schrodinger had to leave Germany after the Nazis seized power.

The Nazis had no problems with Schrodinger but it was Schrodinger who did not like policies

pursued by the Nazis. In fact Schrodinger disgust for the Nazis was so strong that he was

prepared to leave Germany. Initially Scgrodinger thought the Nazi madness will pass over within a

couple of years but soon he realized that the Nazis are going to stay in power for a long time.

Finally Schrodinger left Germany for Oxford. It was possible for intervention of

Frederick Alexander Lindemann (1886-1957), the head of the physics department at

Oxford University and a close friend of Winston Churchill who could persuade

Magdalen College, Oxford, to offer Schrodinger a Fellowship. Lindemann had visited Germany

in the spring of 1933 to try to arrange positions in England for some young Jewish scientists

from Germany. Schrodinger appointment at Magdalen was to be supplemented by a research

appointment in industry so that his income became comparable to that of an Oxford professor.

The confirmation of his appointment was accompanied by the news that he had just been

awarded Nobel Prize in physics, jointly with Paul Dirac. Schrodinger reached Oxford on

November 04, 1933. Lindemann and other tried their best to make Schrodinger stay at

Oxford comfortable. However, Schrodinger was not satisfied with his status at Oxford.

He had received an offer of a permanent position at the Institute of Advanced Studies at

Princeton during his visit there in the spring of 1934 for giving an invited lecture.

However, finally Schrodinger did not accept the offer.

In 1935 Schrodinger’s published a three-part essay on The present situation in quantum mechanics.

It was in this essay the much talked about Schrodinger cat paradox appears. This paradox was a

thought experiment, where a cat in a closed box either lived or died according to whether a

quantum event occurred or not. Schrodinger appointment at Oxford was extended for another

two years. But he did not stay there. He left for his own country Austria to take up an appointment

at the University of Graz. While waiting for the official confirmation of his appointment at

Graz he received an offer of a professorship at Edinburgh. However, the necessary permission

for permanent British residence did not come before the official confirmation came from Graz.

He finally moved to Graz where he was given a full professorship and also an honorary professorship

at Vienna.

While working at Graz, Schrodinger was hoping that eventually he would get an appointment at Vienna.

But this did not happen. In 1938, the Nazis extended their anti-Semitic policies pursued in Germany

to Austria. The newly appointed Nazi Rector of the University of Graz persuaded Schrodinger

to make a repentant confession. The confession began as follows: In the midst of the

exultant joy which is pervading our country, there also stand today those who indeed partake

fully of this joy but not without deep shame because until the end they had not understood the right

course. And it continued in more or less in the same vein. The confession duly appeared in the press.

Many of his friends thought that Schrodinger could write such a confession only under pressure.

But there was no pressure.

Afterwards Schrodinger, of course, always regretted his decision to write such a confession.

Explaining the reason for writing such a confession to Einstein, Schrodinger wrote:

I wanted to remain free — and could not do so without great duplicity.

Schrodinger attended the celebration of the eightieth birthday of Max Plank, where he was warmly

welcomed. But he was no longer acceptable to the Nazi authorities because they did not forget

the insult he caused to them by fleeing from Berlin in 1933. His so-called repentant confession

was of no use. First he was dismissed from his honorary position at Vienna and then on

August 26, 1938 he was also dismissed from his regular post at Graz. The reason cited for his

dismissal was his political unreliability. The official in Vienna, whom Schrodinger consulted,

advised him to get a job in industry. They also told him that he will not be allowed to leave

the country. Schrodinger immediately realized the danger of staying in Austria. So he hurriedly

left for Italy. They had no time even to take their belongings with them. They boarded the train

to Rome with a few suitcases. Schrodingers were received at the station in Italy by Enrico Fermi,

who also lent them some money. From Rome Schrodinger wrote to the Irish statesman

Eamon De Valera (1882-1975), then President of the League of Nations

(predecessor of the United Nations). Schrodinger met De Valera at Geneva.

De Valera offered Schrodinger a position at the Institute of Advanced Studies that he was trying to

set up at Dublin. De Valera also advised Schrodinger to leave Italy at the earliest and go for

Ireland or England, as according to him the war was imminent. Schrodinger accepted De Valera’s

offer of appointment at the proposed Institute at Dublin. However, he did not directly

proceed to Dublin. Instead he went back to Oxford, where he received an offer of one

year visiting professorship at the University of Ghent in Belgium. At Ghent he wrote a

significant paper on the expanding universe. From Ghent Schrodinger alongwith his family went to Oxford.

Lindemann and others who had earlier welcomed Schrodingers at

Oxford was no longer ready to welcome them again. Now Schrodingers were classed as enemy aliens.

But Lindemann made it possible for Schrodingers to reach Dublin in October 1939. Schrodinger

adjusted well in the new environs and under his leadership the Institute of Advanced Studies of

Dublin became an important centre of theoretical physics. He remained in Dublin until he

retired in 1956.

At the beginning of his stay at Dublin, Schrodinger studied electromagnetic theory and

relativity and began to publish on unified field theory. As we know Einstein was also working

on the same problem at the similarly named Princeton University. In 1947 Schrodinger believed

that he had a real breakthrough in his efforts toward creating unified field theory. Schrodinger

was so excited about his new theory that he decided to present it to the Irish Academy without

examining it critically. Schrodinger announcement was widely publicized in the media as an

epoch-making discovery. However, after seeing Einstein comments Schrodinger realized his folly.

He was really devastated by the episode. It was certainly a great embarrassment. After this debacle

Schrodinger turned to philosophy. His study of Greek science and philosophy is summarised in

Nature and the Greeks, which was published in 1954.

Schrodinger most important contribution at the Dublin Institute was his book called

What is Life?.

This was the result of a series of lectures given at the Institute in 1943. The book was published

in 1944. It is regarded as one of the most important scientific writings of the twentieth century.

Francois Ducheseneau wrote: As a contribution to the Dublin Institute series of public lectures,

Schrodinger, who was an engaging speaker, delivered several in February 1943 under the

title: What is Life? In these popular scientific lectures Schrodinger, who had only a very

slight knowledge of the literature on the physical bases of life, dragged his audience into

and then out of a series of blind alleys, leaving them at the end just about where he began.

Nonetheless these lectures, printed the following year, achieved an immediate and great reputation

with both physicists and biologists, and rank still today as one of the most overrated scientific

writings of the twentieth century. The book influenced a good many talented young physicists

particularly those who were disillusioned by the destruction caused by atom bombs in Japan and

wanted no part in atomic physics. Schrodinger showed these physicists a discipline, which was

free from military applications and at the same time very significant and largely unexplored.

The book represented the transfer of new concepts of physics into biology.

Schrodinger presented a determinist vision of the role of genes. He wrote: In calling the structure

of the chromosome fibers a code-script we mean that the all-penetrating mind, once conceived by

Laplace, to which every causal connection lay immediately open, could tell from their structure

whether the egg would develop, under suitable conditions, into a black cock or into a speckled hen,

into a fly or a maize plant, a rhododendron, a beetle, a mouse or a woman.

It was Schrodinger who first used the word

code to describe the role of gene.

He also observed that with the molecular picture of the gene it is no longer inconceivable

that the miniature should precisely correspond with a highly complicated and specified plan of

development.” The book with such passages, written with more insight than that contained in most

contemporary biochemical works inspired a generation of scientists to look for such a code and

which was eventually found. The book helped to shape the discipline that we call today molecular

biology. Michel Morange wrote: Schrodinger book was a remarkable success. Many of the founders of

molecular biology claimed that it played an important role in their decision to turn to biology.

Gunther Stent, a geneticist (and a historian of genetics), has argued that for the new biologists

it played a role like that of Uncle Tom Cabin. Schrodinger presented the new results of genetics

in a lively, the book has lost none of its seductiveness: its clarity and simply make it a pleasure

to read.

In 1955, Schrodinger returned to Vienna. On his arrival he was treated as a celebrity.

He was appointed to a special professorship at the University of Vienna. Though he retired from

the university in 1958, he continued to be an emeritus professor till his death. In Vienna he

wrote his last book describing his metaphysical views.

Schrodinger died on January 04, 1961. Commenting on Schrodinger personal traits his

biographer Walter Moore wrote: Schrodinger was a passionate man, a poetic man, and the

fire of his genius would be kindled by the intellectual tension arising from the desperate situation

of the old quantum theory…It seems also that psychological stress, particularly that associated with

intense love affairs, helped rather than hindred his scientific creativity.

1. Erwin Schrodinger. What is Life?: With Mind and Matter and Autobiographical Sketches.

(Cambridge University Press, 1992);

2. William T. Scott. Erwin Schroedinger: An Introduction to his Writings. University of Massachusetts Press. 1967. 175pp.

3. Dr. Subodh Mahanti.

Erwin Schrodinger. The Founder of Quantum Wave Mechanics.

4. C. Cohen-Tannoudji, B. Diu, F. Laloe: Quantum Mechanics. Two Vols. (Wiley, 1977);

5. J. J. Sakurai: Modern Quantum Mechanics. Revised Edition (Addison Wesley, 1994);

6. B. H. Brandsden, C. J. Joachain: Quantum Mechanics. 2nd edition (Prentice Hall, 2000);

7. D. I. BLOKHINTSEV, Quantum Mechanics, Dordrecht, Reidel, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. 1964;

8. Jagdish Mehra. Erwin Schroedinger and the Rise of Wave Mechanics. (New York: Springer-Verlag. 1987) 392pp;

9. V. V. Raman, P. Forman: Why was it Schroedinger who developed de Broglie ideas?

Historical Studies in the Physical Sciences 1 (1969), 291;

10. L. Wessels: Schroedinger route to wave mechanics. Studies in the History and Philosophy of

Science. 10 (1977), 311;

11. H. Kragh: Erwin Schroedinger and the wave equation: the crucial phase. Centaurus. 26 (1982),

154;

12. M. Jammer: The Conceptual Development of Quantum Mechanics. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins

University Press, 1966);

13. J. Mehra and H. Rechenberg: The Historical Development of Quantum Theory. (New York:

Springer, vols. 1-6);

14. Schrodinger, Centenary Celebration of a Polymath.

Editor Clive William Kilmister,

(CUP Archive, 1987); ISBN 0521340179, 9780521340175;

15. Walter J. Moore, Schrodinger: Life and Thought (Cambridge University Press, 1992);

16. Michel Bitbol. Schroedinger's Philosophy of Quantum Mechanics. (Dordrecht,

Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. 1996), 285pp.

17. W. L. Reiter and J. Yngvason, (eds.),

Erwin Schrodinger - 50 Years After (European Mathematical Society, 2013).

===========================================================================

PDF FILE OF THIS PAGE: SCHRODINGER_ERWIN